Abstract

This study examined the effectiveness of a career intervention class on college students’ career decision making and commitment. The Career Decision Scale was administered at the beginning and end of a semester-long class to 37 college students. The pre- and post-test of the CDS showed significant improvement on certainty and decreased career indecision. The results also demonstrated that students satisfactorily developed concrete academic and career plans, along with relevant action steps towards implementing these plans, after completing the class. The implications for helping college students make career decisions and plans are discussed.

Keywords: career indecision, career intervention, college students

Examining Effectiveness of Curricular Intervention on Career Decision-Making

Students arriving on a college campus are often in the midst of emerging adulthood, defined as the developmental stage between adolescence and the mid-to-late 20s (Arnett, 2000). This life stage is characterized by change and the exploration of possible directions for life in work, love, and worldview (Arnett, 2000). Particularly in the area of work, emerging adults can struggle with career decisions as time is needed to explore a variety of directions (Viola, Musso, Inguglia, & Lo Coco, 2016). Traditional-aged students embarking on the college experience developmentally fit within the exploration stage of career development, wherein an individual is focused on exploring potential career paths, acquiring skills, and making decisions relevant to their career (e.g., identifying career goals, making a plan to reach achievement; Lent & Brown, 2013).

Choosing a career can be particularly challenging for young adults who lack readiness or knowledge or are unsure how to reconcile inconsistent information; some may even struggle to identify the difficulties creating barriers for career decision-making (Amir & Gati, 2006). Choosing a college major is the first step in a series of important career decisions for college students. According to Nauta (2007), satisfaction with one’s major is associated with academic performance and serves as proxy for job satisfaction later on, as similarities exist between the degree program and the future work environment. Students’ satisfaction is dependent upon the fit between themselves and the major in terms of values, interests, and self-concept (Nauta, 2007). Additional factors influencing college major choice include potential for success in the major, effort to complete the program of study, characteristics of instructors, expected career income, prestige, gender, and influences from family and peers (Milsom & Coughlin, 2015; Pringle, DuBose, & Yankey, 2010). Students may also be influenced by the stereotypes they hold about a particular occupation in regards to the personality characteristics and associated skills sets (e.g., the outgoing marketing major or the introverted computer science major); however, these stereotypes are often outmoded or inaccurate representations of the field (Pringle et al., 2010). Therefore, it’s crucial that students get accurate information and exposure to a variety of options to allow them to make informed decisions.

Career indecision refers to difficulties emerging from the career decision-making process and is a normative stage in decision-making which can come and go throughout the lifespan (Lipshits-Braziler, Gati, & Tatar, 2017; Osipow, 1999). Traditional approaches to career development rightfully emphasize “interest, choice, performance, and satisfaction” (Lent & Brown, 2013, p. 558); however, changes in the context of work (e.g., competition on a global scale, economic turmoil, etc.) require innovative approaches in supporting career decisions (Kuron, Lyons, Schwitzer, & Ng, 2015; Lent & Brown, 2013). Contemporary workers need to be prepared to take action and adjust direction as market conditions evolve. The ability to make authentic and strategic career decisions will be increasingly vital for graduates hoping to build thriving careers in our modern economic landscape.

Career courses have been found to be beneficial interventions for students experiencing career indecision, particularly in the higher education setting (Folsom & Reardon, 2003). Completion of a career decision-making class has been found to increase self-efficacy and reduce difficulty making career decisions (Fouad, Cotter, & Kantamneini, 2009). Students with higher self-efficacy are more likely to engage in career exploration behavior (Gushue, Clarke, Pantzer, & Scanlan, 2006). Career exploration can be defined as ‘‘activities directed toward enhancing the knowledge of the self and the external environment that an individual engages in to foster progress in career development” (Bluestein, 1992, para. 3). As career understanding increases, self-efficacy in career-related decision-making and career decidedness also grow (Flum & Blustein, 2000). Courses may result in “a learning curve that is significant in helping students commit to the effort for achieving the best job search outcomes” (McDow & Zabrucky, 2015, p. 635). Engaging in career exploration fosters growth in self-awareness and occupational knowledge, which is particularly important during the exploration stage of late adolescence (Bluestein, 1989). Students who do not successfully complete the tasks associated with this stage may struggle as they enter the workplace (Bartley & Robitschek, 2000).

Though career courses are a well-documented and common approach to reducing career indecision, increasing occupational knowledge, and assisting college students with choosing a major (Reardon & Fiore, 2014), the number of empirical studies conducted in recent years with college students is limited. It remains uncertain whether career courses still benefit this new generation of students in the same ways. In addition, few studies have investigated the efficacy of a 15-week, for-credit course designed to take into account the needs of the Millennial generation. The goal of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of career intervention courses in reducing students’ career indecision and supporting them in choosing a major and creating a career plan with both short-term and long-term objectives. The research questions of this study are: 1) Would career indecision be reduced as a result of taking a one-semester career preparation course? 2) Would college students increase certainty in making career plans as a result of taking a one-semester career intervention course? 3) Would a one-semester career intervention course be effective in helping students create a concrete career plan?

Method

Participants

There were 37 participants, including 24 first-year students, 7 sophomores, and 6 juniors and seniors, at a large urban Midwestern university. The majority of the participants were White and a small number were racial minority students. Twenty-one participants identified as women and 16 identified as men. Although participants’ exact ages were unavailable, the majority were traditional college-age, between 18 and 24 years of age. These students were referred into the course by their academic advisors in order to receive support for their major and career decisions and planning.

Measurement

The Career Decision Scale by Osipow, Carney, Winer, Yanico, and Koshchier (1976) was used to measure the participants’ career decision capacity. The CDS has a total of 18 items on a 4-point scale, which assess how accurately each statement captures participants’ feelings and beliefs about their careers. For instance, participants indicate whether or not a statement such as the following: “Several careers have equal appeal to me. I’m having a difficult time deciding among them” represents their feelings about career. The subscale of Indecision is calculated based on participant responses to 16 items designed to capture career indecision, and the subscale of Certainty is calculated based on two items designed to assess career certainty (Osipow, 2008). The CDS has been widely used in career practice and research as a criterion measure in evaluating career intervention outcomes, and has shown sufficient reliability and validity at various settings with diverse populations (Feldt, 2013; Osipow & Winer, 1996). According to the CDS manual, the reliability for test-retest correlations was at .90 and .82 for the Indecision Scale for two separate samples of college students. For this study, the Cronbach’s Alpha for the Certainty scale is .924 (pre-test) and .63 (post-test); and for the Indecision scale it is .68 (pre-test) and .84 (post-test).

The final assignment in the course, an Education and Career Plan, required students to reflect on their identities, interests, skills and values in order to select a major and was used to measure whether students were able to develop a personally meaningful academic and professional plan. The paper was a 3-4 page essay, designed to incorporate each element of the course and encourage students to identify several concrete short- and long-term goals for their educations and careers.

The assignment comprised six sections. The first asked students to indicate which major they selected, or planned to select, and why they chose that program. The second asked students to indicate their intended career choice and how this may or may not reflect their career assessment results. The third, fourth, and fifth sections asked students to describe short-term, long-term, and occupational goals (respectively) that they hoped to achieve. These sections required detailed explanations of how, and by what date, they planned to achieve these goals. The last section asked students to describe what specific barriers they anticipated in pursuing their educational and career goals, and how they planned to navigate these challenges.

The research team examined the course evaluation to understand how participants perceived their learning experience in the class. The evaluation was a 2-page, 11-item survey designed to assess the efficacy of the curriculum, the quality of instruction, and students’ overall level of satisfaction with the course. As part of the evaluation, students were asked to rate the value of each component of the course on a Likert scale, and describe in what ways the course did or did not help to prepare them for professional success.

In addition, the instructor recorded field notes to better understand how the course impacted students from a teaching perspective. Instructor observations and reflections were captured for each course session, with particular emphasis on student interest and engagement with each topic.

Procedure

The course, Career Decision-Making, was a semester-long, 3-credit course designed to provide students with the opportunity to explore majors and careers, select an appropriate area of study, and develop a thoughtful post-graduate career plan. The course was taught by a career coach in the university’s center for career services. The course sought: to provide students with the opportunity to reflect on their identities, interests, skills, and values in order to select a major and develop a personally meaningful education and career plan; to encourage the development of communication and networking skills; and to expose students to a variety of different career paths and professionals, empowering them to proactively navigate an increasingly complex professional landscape. The course design included each of Brown et al.’s (2003) recommended components of an effective curricular career intervention: a workbook with written exercises, information about the world of work, modeling, computer-guided assistance, self-report inventories, individualized interpretation and feedback, and attention to building support for career decisions. It was comprised of five modules: an introduction to career development, self-assessment, occupational research, networking, and career preparation and planning.

The course begins with an overview of the career decision-making process – exposing students to a career wheel model that illustrates the circular nature of selecting a best-fit career: collecting information about personality, interests, skills and values, researching potential careers, trying out possible options through shadowing, informational interviews and internships, evaluating fit and, if necessary, beginning the process again. Each student receives a workbook with a collection of resources, course information, and written exercises. To complete the course introduction, an in-class session is dedicated to presenting information on the evolving world of work.

In the second module, students take three self-report inventories: the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (Briggs & Briggs Myers, 2015), a popular personality and career assessment, the Self-Directed Search (Holland, Powell, & Fritzsche, 1994), an interests assesment – and an online, computer-guided assessment called Sigi3 (Valpar International Corporation, 1999), which includes a values inventory and career comparison tool). These results are discussed in class, and students receive a list of recommended careers based on each assessment result. The first major assignment of the course asks students to compare their results and select four careers of interest.

The third module introduces students to O*Net (National Center for O*NET Development), the Occupational Outlook Handbook (U.S. Department of Labor), and a variety of other online tools for career exploration. The second major assignment asks them to conduct occupational research on two of their four careers of interest, and narrow to one career option based on their findings. At the midway point in the course, each student meets with the instructor individually for 30 minutes. This allows students to receive personalized feedback on their assessments and guidance on narrowing their career interests.

The fourth module of the course supports students in building a network of professional support. The class attends a university-wide career fair where students interact with employers. They then participate in a speed-networking activity in class with their peers, and learn to use LinkedIn to connect with alumni and other professionals. The third major assignment is an informational interview project, which requires students to locate a professional working in their chosen field, using the tools they’ve learned in class, and conduct a 30-minute informational interview by phone or in-person. They write a paper describing the interview and present this information to the class.

The last module of the course covers job search preparation topics: interviewing, developing a resume, finding an internship, navigating university career services, and setting concrete professional goals. Guest speakers are brought in from across campus to emphasize opportunities for extracurricular involvement and leadership. Panel sessions are held with local employers from a variety of fields, who discuss the advantages and challenges of their industries and how they ended up in their current roles. To close out the semester, students discuss the importance of goal-setting and complete the final paper, a detailed education and career plan.

The course is intended to be as relevant and engaging as possible. Group activities are incorporated throughout to develop social skills. Students have several opportunities to network with local employers and discuss course themes with each other. Video content is incorporated throughout, including TED Talks and graduation speeches by influential thinkers in career development. There are also sessions on topics of immediate and practical relevance, such as time management, emotional wellness, and financial planning.

The instructor of the course administered the CDS at the beginning of the semester and again at the end of the semester. Final papers were collected through online submission and graded according to rubrics available to the students. Each paper was evaluated based on how thorough, concreate and feasible the students’ career action plan was.

Data Analysis

The CDS pre- and post-test were entered into SPSS along with the demographic information of the participants. Descriptive statistics were performed to summarize the mean and standard deviation of two pre- and post- subscales, gender and grade distribution. A paired sample t-test was performed to determine if there were significant differences between pre- and post-administration of the CDS. The 2 X 2 ANOVA were conducted to examine if there were any differences between gender or grade levels. A bootstrap analysis was performed to address the small sample size. The course evaluation data were reviewed by the research team to obtain general feedback about the effectiveness of the course.

Based on the requirements for the final paper, the research team classified student responses into these categories: career plan (yes or no), career plan or major chosen (e.g., psychology, accountant), reasoning for the choice (good or weak, depending on how clearly students articulated their rationale), concreteness of short-term action plan (yes or no), feasibility of short-term action plan (yes or no), concreteness of long-term action plan (yes or no), feasibility of long-term action plan (yes or no), and barriers to implementation. Two research assistants, trained by the primary researcher, coded the final papers independently. The two sets of codes were reviewed by the research team, who checked for accuracy and consistency of the results and consolidated the codes in case of discrepancy between the two sets.

Results

Descriptive Results

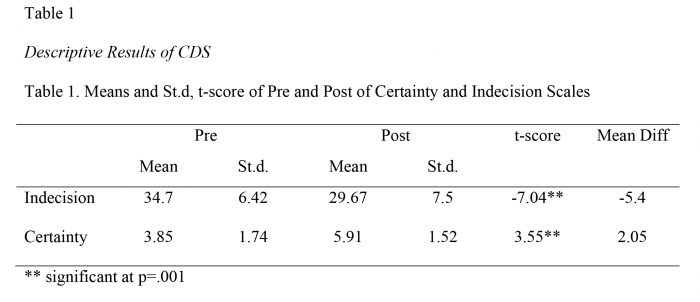

The mean and standard deviation of the two CDS subscales – Certainty and Indecision – are presented in Table 1. The mean pre-test score of the Certainty subscale was lower than the mean of the post-test score, while the mean pre-test score of the Indecision subscale was higher than the score of the post-test. Comparing the pre- and post-test of items 1 and 2, it is clear that students made progress in deciding on a major, but still felt less decided, in the post assessment, on a career. Item 4 indicates that many students are having trouble choosing amongst several appealing careers, suggesting there may be difficulty in committing to a single post-graduate career option. Item 5 asked students if they knew of any careers that appealed to them. In the post assessment, only 3 students of 29 indicated that no careers appealed to them, compared to 10 students in the pre-assessment, suggesting the course was effective in exposing students to new career options.

Several students indicated on the pre-assessment that they agreed with item 7: “Until now, I haven’t given much thought to choosing a career. I feel lost when I think about it because I haven’t had many experiences in making decisions on my own and I don’t have enough information to make a career decision right now.” The majority of these students disagree with this statement in the post-assessment.

In general, students seemed intent on making the “right” career choice. This continued to be true for many, as evidenced by the relatively high agreement on item 10: “I want to be absolutely certain that my career choice is the ‘right’ one, but none of the careers I know about seem ideal for me.” This trend persisted, even after students completed the course and learned about more career options. Similarly, item 11: “Having to make a career decision bothers me. I’d like to make a decision quickly and get it over with. I wish I could take a test that would tell me what kind of career I should pursue” indicates that several students are bothered by the idea of needing to make a career decision and would prefer to be told what choice to make by a career assessment. This remained true for some, even in the post-assessment. Many students persist in their indecision, regardless of exposure to options. It may be that they require something other than information to feel more confident in their decision-making. Incorporating items 13 and 14, which assess students’ knowledge of their abilities and interests, it appears as if lack of self-knowledge isn’t perceived as the main barrier to career decision-making after completing the course. The course had relatively little impact on item 15, “So many things interest me and I know I have the ability to do well regardless of what career I choose. It’s hard for me to find just one thing that I would want as a career.” Most students agreed with this item both before and after the course.

Hypothesis Testing

To determine whether or not the intervention would have any impact on participants’ career indecision, a paired t-test was performed. Results showed that both the t-score for Certainty (t=-7.04, df=33) and Indecision (t=3.55, df=26) were significant with decent effect size (for Certainty .78 and Indecision at .81). The details are illustrated in Table 1. To examine if gender or grade level would impact results on the career decision scale, several 2X2 ANOVA were conducted. Only grade level was found significant (F=11.8 df=2 at the effective size of .43) for the pre-test Certainty scale. Juniors and seniors scored higher in pre-test Certainty than freshmen and sophomore students. Neither gender nor grade level, nor the interaction of the two, was found significant in other ANOVA results.

Results from Qualitative Data

The final paper results supported several of the Career Decision Scale themes. Most students were able to identify a best-fit major, but fewer identified a best-fit career. When asked to articulate both short- and long-term goals, every student was able to name specific and realistic goals, but 40% were unable or unwilling to provide a time frame during which they would complete these goals.

Students identified a wide range of best-fit majors and careers, some more traditional, like early-childhood education or criminal justice, and some less linear, like photojournalism or fashion merchandising. When asked to identify potential barriers to success, the most frequent response was financial barriers (21 out of 36 students), suggesting that students were cognizant of finances and saw this as highly relevant to their career exploration and success. Others mentioned family responsibilities, their own tendency to procrastinate, anxiety, and lack of motivation as potential barriers. Six students out of 39 specifically mentioned health challenges, their own or that of a family member, as a barrier.

The instructor’s notes provided a sense of how and when students were engaging with each topic in the course. It was clear that the specific composition of each cohort of students affected their engagement. Students in the spring cohort occasionally reacted to the same course sessions differently than students in the fall, likely attributable to differences in group personalities and dynamics. A few topics seemed to resonate particularly strongly with the majority of students. Time management and combating procrastination were topics that students asked for specifically. Many also voiced appreciation for the personality and career assessments, confirmed by item 11 on the Career Decision Scale. The idea of having a test steer them in the right direction appealed to many. Some of the first-year students expressed limited interest in job search topics such as interviewing, organizational structures, and values, perhaps considering these sessions less timely than those involving assessment and exploration, given the perceived immediacy of major selection and greater distance to the post-graduate job search. Juniors and seniors expressed more interest in these preparatory topics, especially given that a few of them were applying for post-graduate jobs while enrolled in the course.

The vast majority of students indicated that the informational interview assignment was critical in helping them learn more about their careers of interest, either confirming their choice or eliminating it from consideration. One of the most impactful sessions seemed to be the second class, which set the context for the course by outlining contemporary trends in the world of work. Students showed high engagement with this topic, asked questions, and expressed agreement with or skepticism of the information presented about Millennials and their evolving career expectations. It was clear throughout the course that many students felt pressure, and in some cases anxiety, to make the perfect career decision. Some voiced concern about the tension between their high career expectations and stark financial realities.

Discussion

It has been demonstrated that this curricular intervention showed significant differences in increasing students’ career certainty and decreasing their indecision. As a result of the course, students reported they were more knowledgeable about the professional world and its expectations and more likely to complete their undergraduate education. 30 out of 36 students had selected a major and a few potential careers and mapped out short- and long-term educational and career goals. In spite of these many gains, detailed analysis of the qualitative data indicated a more complex picture.

Contemporary college students’ career expectations are high, with many seeking comprehensive benefits and pay, work/life balance, variety, social impact, and significant personal meaning (Ng et al., 2010; Pinzaru et. al., 2016). These work values tend to remain stable from college through their transition into the workplace (Kuron et al., 2015). While students in this study evidenced increased awareness of their interests and professional opportunities as a result of the course, a significant proportion nonetheless remained unwilling to commit to a single professional career path. It may be, therefore, that students’ high expectations for career, in particular the belief that one’s chosen career should be lucrative, impactful, and personally meaningful, has negatively impacted their ability to choose a single career path at traditional college age.

The results from the qualitative evaluation indicated that even when students successfully identified short- and long-term goals, they were unwilling or unable to provide a timeframe for the accomplishment of these goals, even when this was a required component of the assignment. These data support the idea that some students resist the push to lock themselves into a time-bound career plan, perhaps either preferring to allow for a change of heart or recognizing the inherent uncertainty in today’s job market. This way of thinking mirrors the narratives of the young adults in Davadason’s (2007) study exploring construct coherence within stories of education, employment, and unemployment. The notion of a linear and cumulative working life is downplayed in favor of a life characterized by new experiences, challenges, and continual personal development. Changing jobs, moving on, and avoiding monotony require less explanation in these young adult narratives than job stability and continuity (Davadason, 2007, p. 218).

According to Kuron et al. (2015), “evidence suggests that modern careers are more boundaryless, values- and self-directed than traditional careers” (p. 997). Boundaryless careers can be characterized by movement from employer to employer, free of traditional career organizational boundaries, with emphasis placed upon work agency and choice (Inkson, Gunz, Ganesh, & Roper, 2012). Workers are facing fewer long-term employment guarantees, and opportunities for advancement are diminishing due to downsizing (Baruch & Bozionelos, 2011). As a result, workers often end up seeking new opportunities, either voluntarily or involuntarily, in their pursuit of career advancement. Further, the world of work can be unpredictable due to globalization, outsourcing, increases in temporary and part-time positions, and advances in technology (Sullivan & Baruch, 2009). In this modern environment, career adaptability is defined as “…the readiness to cope with the predictable tasks of preparing for and participating in the work role and with the unpredictable adjustments prompted by the changes in work and work conditions” (Savickas, 1997, p. 254). This may indeed be a critically important career skill. Millennials, in particular, have a strong desire to find meaningful work, and many seek this through the attainment of a college education (DeBard, 2004). Lyons, Schweitzer, and Ng (2015) have found that Millennials are more likely to have increased job and organizational mobility compared with previous generations (e.g., Generation Xers, Boomers, and Matures). Therefore, the period of emerging adulthood is an ideal time to assist contemporary college-aged students in exploring their career options and developing the capacity to adapt to a changing market.

Exposure to yet more information about careers and the economic landscape did not seem to lower students’ expectations for their careers, but rather to create a kind of career paralysis, wherein more information actually limited their willingness to commit to even short-term educational and career paths. The term career paralysis describes the inability to make career decisions for fear of making the wrong one, often the result of feeling overwhelmed by the number of possibilities (Vermunt, 2013). These students’ unwillingness to inadvertently choose the “wrong” career or even to commit to time-bound goals in spite of their newfound self-awareness and knowledge of the working world has implications for how career education might evolve to meet the needs of modern students.

Limitations

Several limitations need to be presented regarding the generalizability of these results. First, this study employed a convenience sample of a relatively small size. Participants were college students in a public, Midwestern, urban setting, and as such, these results might not be replicable with other college students in different settings. Second, the intervention was delivered in a natural setting without control of any possible contributing factors to the participants’ career decision-making; therefore, it should be cautioned not to overstate the impact of the intervention. Third, the design involved a pre- and post-assessment with a time interval of 15 weeks, such that the potential maturation and change of participants throughout this period could impact the results of the post-test. In future research, a larger sample size with national representation would be beneficial to the generalizability of the study. An experimental design would increase the internal validity of the research findings. Moreover, a cross-sectional design including randomly assigned pre- and post-tests would enhance the robustness of the results.

As a final note, because the course is an elective option rather than a requirement, students were most often referred in by academic advisors. These referral conversations were an inherently uncontrollable variable and may have differed between the fall and spring semesters. As always, political and budgetary developments at a large urban university can have unforeseen impact on faculty, staff, and students.

Implications for Career Development Interventions and Future Research

This study provides a number of implications for developing and refining curricular interventions on career decision-making. Offering a for-credit course alongside individualized career services may be more effective than offering optional career services alone. For example, McDow and Zabrucky (2015) found that the majority of students in their control group did not attend career-related offerings on campus, while those enrolled in a career course all attended these offerings as a required component of the course. Participants reported that optional career services events on campus might become a lower priority compared with social activities or more pressing school assignments, and others reported being unsure of the value of these services, choosing not to attend (McDow & Zabrucky, 2015). Further, from students’ point of view, having a career coach as the instructor of their course may provide an ongoing source of career-related advice and support for their future endeavors, a critical element of any effective career intervention (Brown et. al., 2003).

Though this course was open for students of all class years, class standing did impact which aspects of the material students found most valuable. Students in all class years expressed appreciation for the personality and career assessments and self-exploration components of the course. First- and second-year students, however, indicated that they found the job preparation components of the course less valuable, likely because the task of finding a job was perceived as less relevant to their immediate status. These students voiced choosing a major as their more pressing concern, which the assessments seemed to more closely address. In contrast, students closer to graduation expressed more interest in topics related to job search, networking and interviewing, reflecting their proximity to graduation.

Future research might examine the effectiveness of two separate courses, one tailored to the needs of first- and second-year students and one tailored to the needs of juniors and seniors. The earlier intervention might focus more on assessment, time management, maximizing students’ educational experience with experiential learning opportunities and co-curricular involvement, and major selection. The later intervention would then be able to build upon this material, providing tools for post-graduate success such as resume building, information about networking, interviewing, job search and long-term professional success. Very few career interventions examine the longitudinal effects of career courses (Reardon & Fiore, 2014), creating an opportunity to rethink how we measure efficacy of career intervention.

Most students identified the informational interview assignment as the most valuable component of the course. This assignment is one that would likely benefit all students, providing them with an opportunity to expand their networks both for exploration purposes and for their eventual post-graduate job search. It would also lend second-hand knowledge of the specific requirements and working conditions of their tentative career choices. As such, this assignment would be a useful component of any curricular intervention.

There were some pronounced differences in career interests between students in the fall and spring sections of the course. For future courses, it may be useful to assess students’ interests toward the beginning of the course, or to group students by fields of interest, to maximize the relevance of guest speakers and group assignments. While students likely benefitted from exposure to peers with diverse professional interests, it may also be valuable for them to interact with other students and professionals on similar paths.

Any curricular intervention to promote effective career decision-making must build on students’ existing knowledge of work. Experiential learning opportunities – such as internships, co-ops, undergraduate research, service-learning and others – would provide a vital avenue for students to develop complementary skills and knowledge as they solidify an understanding of career. These components, when paired with career education curriculum, would optimally position students for post-graduate success.

Developmental stages need to be considered in the design of this type of curricular intervention. Students in a course of this nature arrive with diverse backgrounds, needs, self-awareness and knowledge of the professional world. As such, assignments and activities should be suitable to their stages of identity and career development. An assignment that may be useful for students in an advanced stage of career development may be counter-productive for a student in a more fundamental stage. Career, including its socio-economic implications, can be closely tied to self-worth and personal identity and, as such, should be approached intentionally. Any curricular intervention should be grounded in relevant theory and best practices.

Conclusion

This study assessed the impact of a curricular intervention on students’ major and career decision-making. The intervention demonstrated effectiveness in reducing career indecision and increasing awareness of the need to choose a major and develop an action plan for entering the workforce. However, though most participants identified a few careers of interest, many demonstrated a reluctance to commit to one long-term career choice.

Future interventions may need to consider the evolving needs of undergraduate students, particularly those students who fall within the Millennial generation. The traditional model of downloading vocational knowledge, though it has historically proven to be effective, may need to evolve to meet the needs and expectations of contemporary students. It may no longer be realistic to expect these students to select and adhere to a single career throughout their working lives, but rather to adapt to the dynamic professional landscape they will inevitably encounter upon graduation.

References

Amir, T., & Gati, I. (2006). Facets of career decision-making difficulties. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 34, 483-503. doi:10.1080/03069880600942608

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469-480. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

Bartley, D. F., & Robitschek, C. (2000). Career exploration: A multivariate analysis of predictors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56, 63-81.

Baruch, Y., & Bozionelos, N. (2011). Career issues. In S. Zedeck, (Ed.), APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Volume 2 (pp. 67‐113). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Blustein, D. L. (1989). The role of career exploration in the career decision making of college students. Journal of College Student Development, 30, 111-117. Retrieved from https://muse.jhu.edu/journal/238

Blustein, D. L. (1992). Applying current theory and research in career exploration to practice. Career Development Quarterly, 41, 74–183. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.1992.tb00368.x

Briggs, K. and Briggs Myers, I. (2015). The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator.

Brown, S. D., Krane, N. E. R., Brecheisen, J., Castelino, P., Budisin, I., Miller, M., & Edens, L. (2003). Critical ingredients of career choice interventions: More analyses and new hypotheses. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62, 411-428. doi:10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00052-0.

DeBard, R. (2004). Millennials coming to college. In M. D. Coomes R. DeBard (Eds.). Serving the Millennial generation: New directions for student services, Number 106 (Vol. 68). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Devadason, R. (2007). Constructing coherence? Young adults’ pursuit of meaning through multiple transitions between work, education and unemployment. Journal of Youth Studies, 10, 203-221. doi: 10.1080/13676260600983650

Feldt, R. C. (2013), Factorial invariance of the indecision scale of the career decision scale: A multigroup confirmatory factor analysis. The Career Development Quarterly, 61, 249-255. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2013.00053.x

Flum, H., & Blustein, D. L. (2000). Reinvigorating the study of vocational exploration: A framework for research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56, 380-404. doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2000.1721

Folsom, B., & Reardon, R. (2003). College career courses: Design and accountability. Journal of Career Assessment, 11, 421-450. doi: 10.1177/1069072703255875

Fouad, N., Cotter, E. W., & Kantamneni, N. (2009). The effectiveness of a career decision-making course. Journal of Career Assessment, 17, 338-347.

doi: 10.1177/1069072708330678

Gushue, G. V., Clarke, C. P., Pantzer, K. M., & Scanlan, K. R. (2006). Self‐efficacy, perceptions of barriers, vocational identity, and the career exploration behavior of Latino/a high school students. The Career Development Quarterly, 54, 307-317.

doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.2006.tb00196.x

Holland, J. L., Powell, A. B., & Fritzsche, B. A. (1994). The self-directed search (SDS): Professional user’s guide (1994 ed.). Odessa, Fl.: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Kuron, L. K., Lyons, S. T., Schweitzer, L., & Ng, E. S. (2015). Millennials’ work values: Differences across the school to work transition. Personnel Review, 44, 991-1009.

doi: 10.1108/PR-01-2014-0024

Lent, R. W. & Brown, S. D. (2013). Social cognitive model of career self-management: Toward a unifying view of adaptive career behavior across the life span. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60, 557-568. doi: 10.1037/a0033446

Lipshits-Braziler, Y., Gati, I., & Tatar, M. (2017). Strategies for coping with career indecision: Convergent, divergent, and incremental validity. Journal of Career Assessment, 25, 183-202. doi: 10.1177/1069072715620608

Lyons, S. T., Schweitzer, L., & Ng, E. S. (2015). How have careers changed? An investigation of changing career patterns across four generations. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30, 8-21. doi:10.1108/JMP-07-2014-0210

McDow, L. W., & Zabrucky, K. M. (2015). Effectiveness of a career development course on students’ job search skills and self-efficacy. Journal of College Student Development, 56, 632-636. Retrieved from https://muse.jhu.edu/journal/238

Mechler, H. (2013). Off our lawns and out of our basements: How we (mis)understand the millennial generation. Journal of College and Character, 14, 357-364. doi:10.1515/jcc-2013-0045

Milsom, A., & Coughlin, J. (2015). Satisfaction with college major: A grounded theory study. The Journal of the National Academic Advising Association, 35(2), 5-14. doi:10.12930/NACADA-14-026

Nauta, M. M. (2007). Assessing college students’ satisfaction with their academic majors. Journal of Career Assessment, 15, 446-462. doi: 10.1177/1069072707305762

Ng, E. S. W., Schweitzer, L., & Lyons, S. T. (2010). New generation, great expectations: A field study of the millennial generation. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25, 281-292. doi:10.1007/s10869-010-9159-4

National Center for O*NET Development. (n.d.). O*NET OnLine. Retrieved November 19, 2017, from https://www.onetonline.org/

Osipow, S. H. (1999). Assessing career indecision. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 55, 147-154. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1999.1704

Osipow, S.H., Carney, C., Winer, J., Yanico, B., & Koschier, M. (1976). The Career Decision Scale (3rd rev.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Osipow, S. (2008). Career decision scale. In F. T. L. Leong (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Counseling (pp. 1469). Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Osipow, S. H., & Winer, J. L. (1996). The use of the career decision scale in career assessment. Journal of Career Assessment, 4, 117-130. doi:10.1177/106907279600400201

Pînzaru, F., Vatamanescu, E. M., Mitan, A., Savulescu, R., Vitelar, A., Noaghea, C., & Balan, M. (2016). Millennials at work: Investigating the specificity of generation Y versus other generations. Management Dynamics in the Knowledge Economy, 4, 173-192.

Pringle, C. D., DuBose, P. B., & Yankey, M. D. (2010). Personality characteristics and choice of academic major: Are traditional stereotypes obsolete? College Student Journal, 44(1), 131-143. Retrieved from http://www.projectinnovation.com/college-student-journal.html

Reardon, R., Fiore, E., & Center, D. S. (2014). College career courses and learn outputs and outcomes 1976-2014 [Report No. 551]. Tallahassee, FL: The Center for the Study of Technology in Counseling and Career Development.

Savickas, M. L. (1997). Career adaptability: An integrative construct for life‐span, life‐space theory. The Career Development Quarterly, 45, 247-259. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.1997.tb00469.x

Sullivan, S. E., & Baruch, Y. (2009). Advances in career theory and research: A critical review and agenda for future exploration. Journal of Management, 35, 1542-1571.

doi: 10.1177/0149206309350082

Tirpak, D. M., & Schlosser, L. Z. (2013). Evaluating FOCUS-2’s effectiveness in enhancing first‐year college students’ social cognitive career development. The Career Development Quarterly, 61, 110-123. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.2013.00041.x

U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.). Occupational outlook handbook. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/ooh/

Valpar International Corporation. (1999). Sigi3 (Version 14) [Computer software]. Retrieved from http://www.valparint.com/siginew/sigi.html

Vermunt, S. (2013). Career paralysis: Millennial meltdown. Forbes. Retrieved from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/85broads/2013/11/15/career-paralysis-millennial-meltdown/#150563574287

Viola, M. M., Musso, P., Inguglia, C., & Lo Coco, A. (2016). Psychological well‐being and career indecision in emerging adulthood: The moderating role of hardiness. The Career Development Quarterly, 64, 387-396. doi: 10.1002/cdq.12073

Zemke, R., Raines, C., & Filipczak, B. (1999). Generations at work: Managing the clash of Veterans, Boomers, Xers, and Nexters in your workplace. New York, NY: Amacom.