What Students, Internship Coordinators and Employers Need to Know about Title IX

Joseph “Mick” La Lopa // Purdue University

Click Here to Download this Article

Abstract

Each year in the United States thousands of college students head out to complete an internship as part of a degree requirement. Students Title IX rights apply to any internship that is required to complete a degree so that students can complete them without being harassed; and if harassed have the support of their internship coordinator and/or Title IX coordinator to stop it. However, two recent studies of hospitality students revealed that it is not common knowledge that students Title IX rights follow them off campus to their internship. This article will provide the key findings of the two studies on sexual harassment of student interns and make recommendations on what students, internship coordinators and employers should do to protect those rights in the future.

Keywords: Sexual Harassment, Internships, Title IX

Introduction

The issue of sexual harassment is now reported daily in the news media. The list of those accused of sexual harassment grows by the day in all aspects of the private and public sector. It is no secret that one of the industries that is rife with sexual harassment is the hospitality industry, especially the food service sector. In fact, more than 14% of the 41,250 sexual harassment claims filed in the USA from 2005 to 2015 were in the food service and hospitality sector (Meyer, 2017). In 2018, a restaurant group that operates two International House of Pancakes (IHOP) franchise restaurants in Southern Illinois paid $975,000 to 18 claimants to settle sexual harassment and retaliation claims filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). Yet, each year hospitality programs routinely require students, who are mostly female, to complete an internship in an industry which is notorious for sexual harassment in the workplace.

In this article I will describe two recent studies that were completed to investigate whether hospitality students Title IX rights were being safeguarded during an internship. As mentioned, Title IX states that, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” The first study was a descriptive one to see if student interns were being harassed. The second one was prompted by the study findings of the first one; it was a qualitative study involving internship coordinators at the top 25 hospitality programs to see what they are doing to protect students Title IX rights during an internship. The findings are relevant to all academic units and businesses that employ interns so recommendations will be made for students, internship coordinators, and employers to protect students’ rights.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment was thrust into the national spotlight when Anita Hill was testifying in 1991 before the Senate Judiciary Committee in a televised hearing about being harassed by Clarence Thomas when she worked for him at the Department of Education. At the time, many of the male Senators on both sides of the aisle were dismissive of her claims and were quite hostile to her unlike the soft treatment given Thomas as to his behavior. Although Hill’s testimony did not stop the Senators from confirming Thomas as a Supreme Court Justice, Congress did take action in 1991 to strengthen Title VII of The Civil Rights Act of 1991. We saw history repeat itself in the 2018 of Christine Blasey Ford, a psychologist who lives in California and teaches at Palo Alto University, who testified before Congress that Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh attempted to rape her when they were at a gathering of teenagers at a Maryland home in 1982. Even though she and other women came forward with similar allegations, the Senate did not take the women seriously enough to vote against giving Kavanaugh a lifetime appointment on the Supreme Court, perhaps signaling to other women that their claims of sexual misconduct on the part of privileged males will be disavowed as well so better to remain quiet.

Perhaps more people are familiar with Gretchen Carlson, a former Fox News anchor, who sued her old boss, Roger Ailes, for sexual harassment. In her suit, Ms. Carlson claimed that Mr. Ailes made sexual advances toward her and later fired her because she complained about sexual harassment at the network (Koblin, 2016). Of course Mr. Ailes denied it. In the end, Ms. Carlson was taken seriously and awarded 20 million dollars and an apology from Fox News. Readers are encouraged to read her book where she shares her own experiences, those of other women, and gives sound advice on what women can do to empower and protect themselves in the workplace or college campus (Carlson, 2017).

The current definition of sexual harassment provided by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission reads as:

“Unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature constitute sexual harassment when: a) Submission to such conduct is made either explicitly or implicitly a term of condition of an individual’s employment, b) Submission to or rejection of such conduct by an individual is used as the basis of employment decisions affecting such individual; or c) Such conduct has the purpose or effect of unreasonably interfering with and individual’s work performance or creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working environment.” (Facts about sexual harassment, n.d.)

Survey after survey makes it clear that the vast majority of sexual harassment perpetrators are men and the vast majority of victims are women (Pryor, LaVite & Stoller, 1993). This is true because men have used their economic power, their positions of authority, and their gender-based power (including the underlying threat of violence as the basis for their ability to harass and intimidate women) for the purposes of “forcing sexual access, enforcing male dominance, and applying strategic harassment to drive women out of male occupations” (Langelan, 1993, p. 71). That is why Langelan (1993) gets more to the point by defining sexual harassment as “the inappropriate sexualization of an otherwise nonsexual relationship, an assertion by men of the primacy of a women’s sexuality over her role as a worker or professional colleague or student.” (p. 34).

Sexual harassment is not a victimless crime; it causes great suffering for those who experience it in the workplace. As (Matulewicz, 2016) points out:

“Sexual harassment is a demeaning practice, one that constitutes a profound affront to the dignity of the employees forced to endure it. By requiring an employee to contend with unwelcome sexual actions or explicit sexual demands, sexual harassment in the workplace attacks the dignity and self-respect of the victim both as an employee and as a human being” (p. 130).

According to Bravo and Cassedy (1992) women can suffer psychological, physical, and economic effects, not to mention the ill-effects imposed on their families and the employer. Psychological effects include self-doubt, denial, self-blame, invalidation, humiliation, loss of interest in work, loss of trust, anger, and depression. Depression alone can lead to lack of appetite causing weight loss, sleep disorders, decreased sex drive, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness, inability to focus, and suicidal thoughts. Women suffer economically because they leave or lose their jobs often times for lower paying jobs in addition to the attorney and doctor fees it takes to file a sexual harassment claim providing they are not fired for taking their complaint to human resources (HR), which is not atypical. The family suffers, too, because someone being harassed at work has to show restraint only to go home and take their emotions out on the family, who do not understand the underlying reasons for the sudden change in behavior. Finally, the company suffers the effects of harassment not only in the millions paid to settle sexual harassment claims, but the loss of productivity, increased absenteeism, higher employee turnover, and the costs associated with hiring new employees.

Sexual Harassment in the Hospitality Industry

According to the US Government’s’ Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) the leisure and hospitality supersector is part of the service-providing industries supersector group, including financial activities and business and professional services. The different sectors of the hospitality industry include food & beverage, lodging, recreation, as well as travel and tourism businesses.

The hospitality industry is one of the largest and fastest-growing sectors in the service industry on the planet (Morgan & Pritchard, 2018). Globally, women comprise 70 percent of the tourism and hospitality workforce but less than 40 percent in managerial positions (Baum & Cheung, 2015). According the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the leisure and hospitality industry employed over 16 million people at the end of 2017 (Industries at a glance, n.d.).

Sexual harassment continues to be a major problem in the hospitality industry (Madera, Guchait, & Dawson, 2018) not only for restaurant servers but housekeepers in hotels as well (Kensbock, Bailey, Jennings, & Patiar, 2015). Despite the laws and legislation that have been enacted to prevent it 10-20% of workers report experiencing bullying, violence and sexual harassment in the workplace (Ram, 2018).

One of the underlying causes of harassment in restaurants is due to the fact that employees work in spaces where people go to socialize with friends, family, co-workers, and others. Unfortunately, these social spaces are renowned for having sexualized work environments where sexual harassment is rampant, if not encouraged by the restaurant culture (Poulston, 2007 & Leyton, 2014). Restaurant employees do their jobs when others are socializing and having a good time while they work nights, weekends, and holidays and become separated from their normal social and sexual activities creating a subculture that has a special bond perpetuating the sexualized work environment (Anders, 1993). Female servers, especially, have to contend with male managers who are told to look their best, watch their weight, dress as though date ready, wear push up bra’s, shorter shorts, and more to essentially invite harassment from customers (Covert, 2014). Or, as Guiffre &Williams (1994) puts it, “waitresses are expected to be friendly, helpful, and sexually available to the male customers…consequently some women are reluctant to label blatantly offensive behaviors as sexual harassment (p. 386-387).

One key aspect of the food and beverage industry is that servers depend on tipping to earn a living. Servers are at the mercy of the customers because they hold economic power over them in the form of tips, which they depend on to earn a living. That dilemma forces servers to endure endless inappropriate verbal and physical behaviors which makes a high stress job that much more difficult due to harassment (The Glass Floor, 2014). Verbal behaviors which include sexual teasing, jokes, remarks about sexual orientation, flirting, and being told, as mentioned above, by managers to wear tighter/revealing clothing that expose oneself sexually. Physical behaviors include pressure for dates, sexually suggestive looks and gestures, deliberate touching, cornering, pinching, attempts at kissing or hugging, patting, fondling, being ask to sit on one’s lap, and more.

Hospitality Internships

A sufficient reason for the wrongness of sexual harassment in higher education is “that the harassment of any person or group for any reason – sexual, religious, ethnic, racial, etc. – jeopardizes the conditions under which learning can take place” (Holmes, 2001, p. 187). As such, there must be confidence on the part of all students that professors, staff, fellow students, and others will not exploit that trust in them for their personal gain and harassing a student in any way violates that trust. To enable a student to obtain an education without harassment, Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972 is a federal law that states, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Title IX rights do apply to students when participating in academic activities that are part of a degree plan. The Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR), guidelines make it clear that education programs and activities covered by Title IX include “any academic, extracurricular, research, occupational training or other education program or activity operated by the recipient” (Bowman & Lipp, 2000, p. 115).

In addition, Universities are required by the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) to:

“…develop and implement procedures regarding sexual harassment of students during educational programs that are not operated wholly by the school, as in the case of internships, and to refrain from cooperating with outside organizations known to discriminate…and that the University is obligated to provide a prompt, thorough and equitable investigation of any report of sex-based discrimination, sexual harassment or sexual violence. This obligation remains even in the absence of a formal complaint.”

Therefore, internship coordinators not only need to inform students that their Title IX rights follow them off campus; they must prepare students to handle any situation where their rights are potentially being violated during the course of an internship. They do not bear this responsibility alone; they have the support of the Title IX coordinators on campus, who are required by the statute, to investigate complaints of sexual harassment made by students during their internship.

According to Zopiatas and Constanti (2012), an internship is defined as “a structured and career-relevant supervised professional work / learning experience, paid or unpaid, within an approved hospitality company/organization under the direct supervision of at least one practicing hospitality professional and one faculty member, for which a hospitality student can earn academic credit” (p. 44).

Internships are designed to connect the classroom to the industry where students can apply what they learned in the context of the myriad of businesses and acquire hands-on learning working for those businesses that are part of the hospitality industry. According to Self, Adler and Sydnor (2016), students who completed an internship: a) enjoy greater job satisfaction, b) obtain initial employment more quickly, c) report higher starting salaries than those students not participating in a college internship, d) apply classroom material/theory to real world situations, e) develop skills such as problem solving, critical thinking, and networking, and f) become more familiar with the industry. Employers also benefit from student internships because they: a) provide a trial period as they offer a low-cost opportunity to work with a perspective employee providing labor hours to the company, b) act as a realistic job preview, which has been shown to set realistic job expectations, helps reduce thoughts of quitting, and increases job survival for new hires, and c) spread positive word of mouth about the business to recruit future interns if the experience was a positive one. Institutions also “benefit from internships by the ability to advertise their relationships with the industry to potential students and parents, increase the school’s visibility, and in the long term help build loyalty from former students due to successful placements” (Self, et al. 2016).

Research into other academic fields where students complete internships also finds incidences of sexual harassment. A study conducted by Kettl, Siberski, Hischman and Wood (1993) found that 40 percent of the 158 nursing and occupational therapy students who participated in the study endured sexual harassment of a verbal or sexual nature; sexual innuendo (40%) was the most common form while verbal requests for a sex act the least common (22%). As reported in other studies, students chose to ignore the harasser or joke about it which proved to be a successful coping mechanism to handle the harassment about 85 percent of the time. Since the time of the 1993 study, not much has improved for nursing interns given Seun Ross, Director of Nursing Practice and Work Environment at the American Nurses Association, who was quoted as saying:

“The topic of sexual harassment needs to be addressed throughout nurses’ careers: in nursing school, during internships, and in the workplace. The onus is on the educators – the professors, the dean, the chief nursing officer – that this kind of behavior will not be tolerated and it is safe to report it.” (Nelson, 2018, p. 19).

Nelson, Rutherford, Hindle and Clancy (2017) re-administered their Survey of Academic Field Experiences (SAFE) that established the fact that scientists, particularly during trainee stages, experience sexual harassment and sexual assault while conducting field work. The second SAFE study surveyed 666 respondents who had conducted field research across life, physical and social sciences. Examples of sexual harassment included “unwanted flirtation or verbal sexual advances, field site manager insisting on conducting conversations while naked, propositions, and jokes about physical appearance or intelligence that were sexually motivated or gendered” (Nelson, et. al., 2017). Sadly, most of those interviewed said they were not in a position to say no and women resorting to hiding, leaving, or confronting offenders did not deter the site director leaving the researchers to conclude that until codes of conduct (rules) coupled with accountability for transgressions (consequences for sexual harassment) are adopted and rigorously enforced women will continue suffer at the hands of males wielding social and economic power during their field work.

TWO STUDIES ON PROTECTING STUDENTS TITLE IX RIGHTS

Study 1 – Descriptive Study of Sexual Harassment of Hospitality Students

The purpose of the first descriptive study was to determine whether or not US hospitality students were sexually harassed during an internship. The following questions were asked to determine whether students’ Title IX rights were being protected during an internship, namely: a) did female students experience sexual harassment more than their male counterparts?, b) who was harassing students?, c) what actions did students take in response to harassment?, d) were students informed as to the forms of sexual harassment they may encounter during an internship?, and e) were students trained by the internship coordinator or the employer to handle sexual harassment if experienced during the internship?

The sample consisted of students enrolled at four hospitality programs that are typically ranked among the top ten in the United States, according to Brizek & Khan (2002). An e-mail with a link to the survey was sent out several times (one week apart) to those students who had completed an internship within the past year by their internship coordinator to boost response rates. The e-mail also described the purpose of the study, what students were being asked to do, a statement on confidentiality, risks and benefits, and that participation was voluntary.

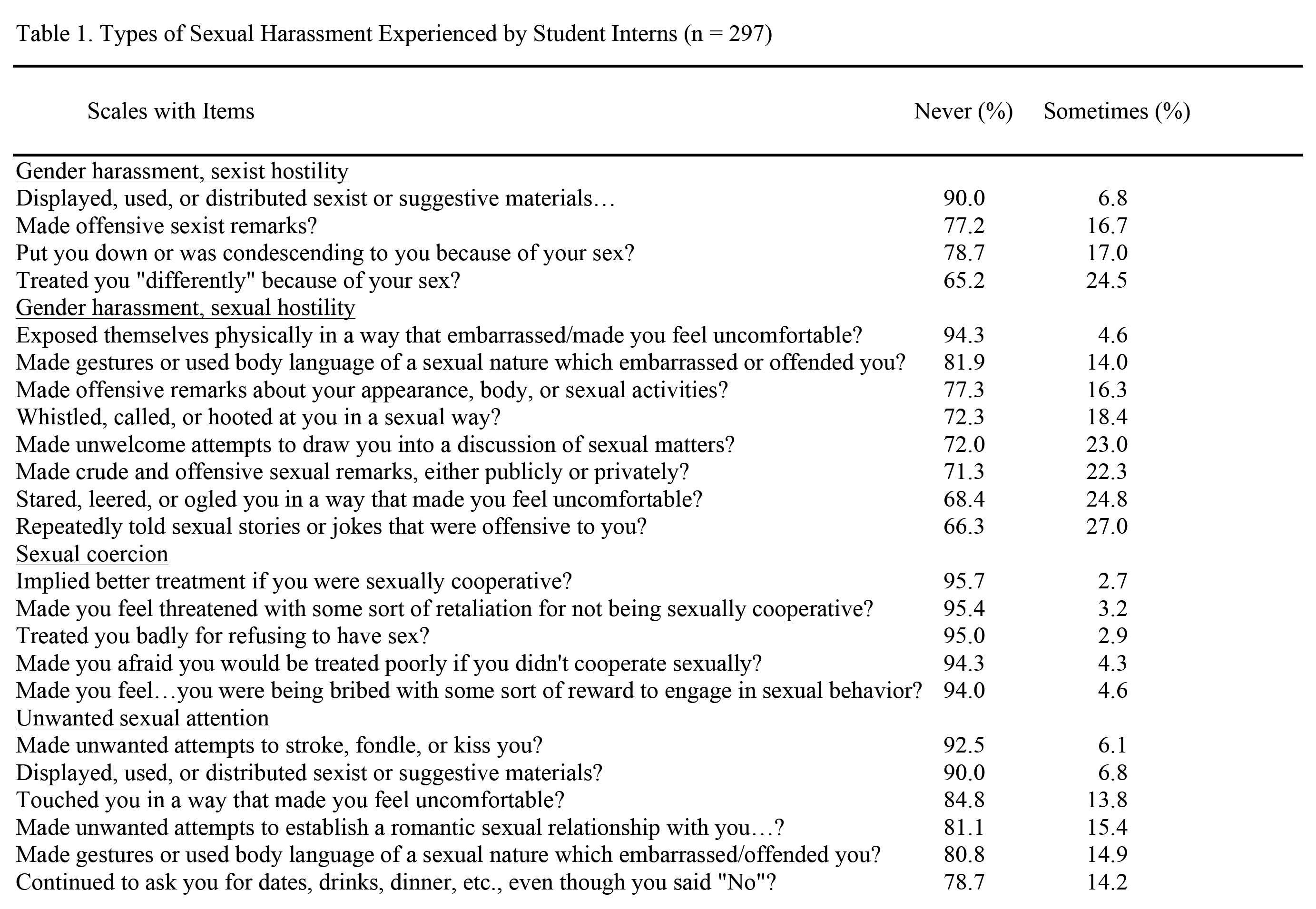

The survey instrument used to determine if students were being sexually harassed during internships was based on a study conducted by Fitzgerald, Magley, Drasgow, and Craig (1999). The instrument, known as the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire (SEQ) was developed to investigate sexual harassment of women in the military. The SEQ is broken into four categories, namely: a) gender harassment, sexist hostility, b) gender harassment, sexual hostility, c) unwanted sexual attention, and d) sexual coercion. Gender harassment (sexist and sexual hostility) is defined as mostly verbal and nonverbal behaviors that convey degrading, hostile and insulting attitudes about women. Unwanted sexual attention was defined as verbal and nonverbal behavior that is deemed offensive, unwanted and unreciprocated. Sexual coercion was defined as pressuring someone into doing sexual favors in return for job-related perks and rewards, which is class quid quo pro harassment (something for something). Respondents indicate the degree of harassment on a 5-point Likert Scale, from 1 “Never” to 5 “Always.” The four scales and their items for the SEQ are found in Table 1.

In addition to the SEQ, students were asked if harassment came from: a) female managers, co-workers, or customers and/or b) male managers, co-workers, or customers. To determine if students suffered physical and psychological effects due to harassment they were asked if they found it difficult to do their job as a result of harassment. Students were also asked to indicate what actions, if any, they took in response to harassment.

Due to the reputation of the hospitality industry for sexual harassment, it was important to determine if students were being informed as to the inappropriate behaviors they may encounter during an internship. Students were also asked if they were given training by the internship coordinator or employer on what to do if harassed.

The survey concluded with questions concerning the demographics of the respondents, including: a) the program they were attending, b) gender, c) the sector of the hospitality industry where they did their internship, d) racial/ethnic group, g) grade level, h) whether member of LBGTQ community, i) international or domestic student, j) and age.

There was an overall response rate of 36% from the 786 students from the four universities who were invited to participate in the survey. The sample was comprised mostly of female students (75%), which fit the demographic of today’s hospitality programs that are dominated by female students. Just over half of the students (50.7%) were age 21 (28%), and 22 (22.7%), respectively. The racial/ethnic group of the sample was comprised of Caucasian students (45.8%), followed by Asian students (34.7%), then Hispanic/Latino (13.5%) and African American (3.4%). The majority of respondents were seniors (74.5%) and juniors (18.5%), which is typically when students complete their internships. A small percentage of the sample (6.8%) indicated they considered themselves a member of the LBTGQ community. Only 16% of the sample was comprised of international students.

Fortunately, the majority of those who participated in the study indicated that they “never” experienced sexual harassment of any kind during their internship. As show in Table 1, students did encounter aspects of “Gender harassment, sexist hostility” and “Gender harassment, sexual hostility” but did not encounter “Sexual coercion” during their internship. With respect to “Gender harassment, sexist hostility,” the behavior with the highest incidence experienced by students, was “treated you differently because of your sex,” (24%). With respect to “Gender harassment, sexual hostility,” the behaviors with the highest incidence experienced by students, was: a) “Repeatedly told sexual stories or jokes that were offensive to you?” (25.8%), b) “Stared, leered, or ogled you in a way that made you feel uncomfortable?” (23.9%), and “Made crude and offensive sexual remarks, either publicly (for example, in your workplace) or to you privately?” (22.1%).

Female students did experience harassment significantly higher than males in a few cases with respect to: a) “Treated you “differently” because of your sex,” b) “Made offensive sexist remarks,” c) “Put you down or was condescending to you because of your sex?” and d) “Stared, leered, or ogled you in a way that made you feel uncomfortable?” However, male student interns were harassed significantly higher than females when it came to “Exposed themselves physically in a way that embarrassed/made you feel uncomfortable.”

It came as no surprise that female student interns who indicated they experienced harassment were harassed by male managers (26.7%), male co-workers (52%), and male customers (44.8%).

When we isolated only those students who reported they felt strong emotions “slightly,” “moderately,” or “mostly” in response to harassment; there were 39.3% who experienced such emotions even when they “slightly” experienced “offensive sexist remarks” or when someone “displayed, used, or distributed sexist or suggestive materials.” When we isolated only those students who experienced various forms of sexual harassment “slightly” or “moderately” there were 39.3% who reported they “slightly” found it difficult to do their job when someone: a) “Displayed, used, or distributed sexist or suggestive materials,” b) “Made offensive remarks,” and/or c) “Whistled, called or hooted in a sexual way.”

It came as no surprise that students who experienced harassment did what most victims do, for any myriad of reasons, they opted not to take action to deal with it. Instead, students tended to avoid the person responsible for the harassment (14%), ignored the behavior or did nothing (13.7%), or reported it privately to family, friends, and others. A small percentage of the sample asked the person to stop (10.8%), reported it to their manager (5.9%), reported it to human resources (3.1%), or reported it back to their internship coordinator (2%). Six students actually left the company as a result of the harassment but there was not a follow up question on the survey to ask if they reported it to their internship coordinator.

An overwhelming majority of respondents (81%) indicated that they were not given any fair warning as to the inappropriate sexual behavior they may encounter during their internship, regardless of the sector where it was to be completed. There were 57% of respondents who reported they were not given any training on how to handle sexual harassment during their internship. The majority of respondents indicated that more than half of employers (53.4%) did not provide any training/information by their manager (or anyone else in the organization where they did their internship) on what they should do if they encountered sexual harassment during their internship.

Study 2 – Qualitative Study of Internship Coordinators

Two key study findings jumped out in particular from the first study which prompted a second qualitative study involving internship coordinators. The first key finding was that a majority of students reported that they were not informed as to the inappropriate sexual behaviors they may encounter during their internship in an industry renowned for sexual harassment. The second was that over half of the students reported they were given no training by the internship coordinator or the employer to handle harassment.

To conduct the second study, a graduate student from a large Midwestern University identified the top 25 hospitality programs as reported by TheBestSchools.org (The Thirty Best Hospitality Programs, n.d.). The student then prepared a spreadsheet with the contact information for those responsible for managing student internships to participate in the study.

To begin the qualitative study, I went to the website of each of the hospitality programs to search for information on internships pertaining to Title IX. An e-mail was then sent to all those responsible for student internships inviting them to participate in the study. Each internship coordinator was then called to complete a short phone interview. In some cases it only took one phone call to complete an interview, in some cases it took as many as four phone calls to get to the person responsible for internships to participate, or not, in the survey.

The interview of internship coordinators consisted of the following questions: a) “Do you have a mandatory orientation where students are informed of their Title IX rights during internship and what to do if they are violated?,” b) Do you have an internship manual for students? May I have a copy?,” c) “Do you have a template letter that is sent by employers that mentions Title IX rights? May I have a copy?,” d) “Is there a dedicated person during internships to field calls for any kind of abuse or problems?,” and e) “Has a student(s) ever reported or claimed sexual harassment during an internship or upon returning to campus?”

As mentioned, prior to the interviews a review of each programs websites was audited for information pertaining to their internship programs. The review found a wide variability of content for students and employers who may be interested in hiring interns. Several of the websites had cursory information about the internship requirements while others had very detailed information on the definition of an internship, its purpose, the requirements to obtain one, the number of hours required to complete it, procedures for securing one, and supplemental materials outlining student conduct/responsibilities during the internship. Only one website made any mention of students Title IX rights during an internship, which was my program, given my research on sexual harassment of student interns.

The next phase of the study was to conduct the phone interviews. There were 21 of the 25 internship coordinators who participated in the study. Two of the internship coordinators could not be reached and two declined to participate in the survey.

The question of whether students were required to attend a mandatory orientation that included informing students of their Title IX rights turned out to have a two part answer. There were only six programs that required students to attend a mandatory orientation that would be designed to prepare them to successfully complete an internship; the rest are apparently left to their own devices when it comes to navigating the internship waters. Only three of the respondents indicated that they informed student interns of their Title IX rights; the rest, in many respects, did not realize those rights followed students off campus (but they know differently now). The reason two of the three coordinators inform students of their Title IX rights was due to their survey of student interns that found they were harassed during an internship and took measures to protect those rights. It is worth noting that those surveyed are now giving more thought to informing students of their Title IX rights and finding a way to train them to handle harassment.

When asked if there was an internship manual for students that they would share for the study, there were seven respondents who reported they did have an internship manual or guidebook for students (one was available online for students), but did not offer to share as part of this study. Out of the seven, four included the manual as a part of their course syllabus.

When asked if there was a template letter required of employers that mentions Title IX rights and if so, share a copy, only one of the respondents indicated there was a template offer letter that has the employer acknowledge that the students Title IX rights follow them off campus, which was again my program given what we learned from the first study. There were a couple programs that have the employer and student sign an internship contract but there was no other program that requires language on Title IX.

When asked if there was a dedicated person that students could contact if experiencing harassment during their internship, 18 of the respondents indicated that there was a dedicated person for students to call if they were experiencing problems, such as harassment, during their internship. The contact person could be a member of the staff, the internship coordinator, a dedicated faculty member, or general contact person. One respondent made an alarming statement that, “there is not a dedicated person but they should know who to contact if they have a problem.” Fortunately the majority of respondents indicated that there was a dedicated person for students to contact, but what was troubling is that if students are not informed of their Title IX rights how likely are they to report a violation in the first place?

When asked if students have ever reported sexual harassment during an internship, there were ten internship coordinators who indicated that harassment has been reported by student interns. For confidentiality purposes they did not provide specifics but all reported only a few minor instances out of hundreds of students who have completed internships. One internship coordinator indicated a student had to be removed from her place of employment due to harassment and placed with another employer. However, this finding does not necessarily mean that there were not more students who were harassed during an internship since victims tend to remain silent when they are harassed and adopt various coping/avoidance strategies to avoid the harasser.

GOING FORWARD TO PROTECT STUDENTS TITLE IX RIGHTS

Recommendations for Students, Internship Coordinators and Employers

As indicated, the purpose of the two studies was to first determine whether students Title IX rights were being protected, and the second one sought to determine what hospitality programs were doing to protect those rights. The study findings suggest that students are being sexually harassed during their internships – to various degrees – and much more needs to be done by internship coordinators and employers to protect those rights. Although this study was based on the academic field of hospitality and tourism management, it may very well be the case that students attending other degree programs – especially those dominated by females – are not being adequately prepared to handle harassment during an internship that is required to complete an academic degree, which is a violation of their Title IX rights. Such being the case, there are things that students, internship coordinators, and employers can do to help protect Title IX rights.

With regards to students, most universities and colleges have mandatory Title IX training for students at the start of the fall semester to make sure they know they have a right to an education free of harassment and remedies for harassment. Some will not even let students register for classes until the training is completed. Whether they know Title IX rights follow them off campus or not, students should report harassment to the internship coordinator, who is a “mandatory reporter,” meaning that complaint must be turned over at once to a Title IX coordinator who will then investigate the situation and resolve it on behalf of the student.

There are five key things that internship coordinators must start doing to protect student’s rights, which we adopted in the School of Hospitality and Tourism Management as a result of my research. These five things have proven to be successful to protect our students’ Title IX rights so they are not based on conjecture. The first thing to do is to create a comprehensive orientation manual, that includes information on Title IX rights, and require students to attend a mandatory orientation to make sure they understand what it takes to successfully complete an internship.

Second, there should be a template offer letter for employers that include language that they are aware of students Title IX rights and that those rights will be protected during the internship. That letter will go a long way to both remind the students of their rights and put the onus of protecting those rights on the employer. For example, our internship coordinator requires every employer to have the following language in their offer letter:

“We are aware that Title IX states that “”No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subject to discrimination under any educational program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Since an internship is considered an off-campus academic activity we will be sure to safeguard the students Title IX rights during the student’s internship with our company.”

Employers must have no problem signing an offer letter that includes language on Title IX. They should also have an orientation with students before they start working to inform them of their sexual harassment policy and trained on what to do if they are harassed. Those employers who choose otherwise may be subject to a Title IX violation investigation by the University/College the student is attending, which may lead to the removal of current interns, and/or denied the chance to recruit interns in the future by the internship coordinator. Surely, the #MeToo Movement has made it clear to employers that the onus is on them to create a safe workplace for not only those student interns, but all employees, because #Times Up.

Third, during the orientation students should be informed as to the inappropriate behaviors they may encounter during an internship (that constitute both sexual and non-sexual forms of harassment) and trained on the procedures they should take to handle it, which does not include ignoring the behavior of the person doing it, because they have the right to an internship free of harassment. I am currently doing that training before our students depart for their internships. In reality, the decision for internships coordinators to start training student interns of their rights and how to handle harassment is not simply a good idea; they are required by the Office of Civil Rights (OCR), “to develop and implement procedures regarding sexual harassment of students during educational programs that are not operated wholly by the school, as in the case of internships, and to refrain from cooperating with outside organizations known to discriminate.” Thus, every academic unit that is not currently training students to handle harassment during an internship – that may or may not be known for sexual harassment – is potentially subject to a Title IX claim if a student chooses to hold them responsible for not warning them of potential harassment and how to handle it.

Fourth, student interns should be surveyed during their internship. I first worked with our internship coordinator to survey whether students experienced the various forms of sexual harassment listed on the SEQ after they returned from their internship. We realized that surveying students after the fact was too late so because it was too late to do anything about it. It is important to note that we have now added non-sexual forms of harassment that may be inappropriate commentary about one’s race, age, religion, ethnicity or gender identification based on previous student surveys.

As an end note; I am happy to provide copies of all our materials pertaining to student internship materials upon request.

References

Anders, K. T. (1993). Bad Sex: Who’s Harassing Whom in Restaurants? (Sexual Harassment in the Restaurant Business) (Includes Related Article on Prevention). Restaurant Business. Retrieved from https://business.highbeam.com/137339/article-1G1-13615346/bad-sex-harassing-whom-restaurants

Baum, T. & Cheung, C. (March, 2015). White Paper Women in Tourism & Hospitality:

Unlocking the Potential in the Talent Pool. Retrieved from: https://www.diageo.com/PR1346/aws/media/1269/women_in_hospitality___tourism_white_paper.pdf

Bowman, C. G., & Lipp, M. (2000). Legal limbo of the student intern: the responsibility of colleges and universities to protect student interns against sexual harassment. Harvard. Women’s LJ, 23, 95.

Bravo, E. & Cassedy, E. (1992). The 9 to 5 guide to combating sexual harassment: Candid advice from 9to5, the national association of working women. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Brizek, M.G. & Khan, M.A. (2002) Ranking of U.S. Hospitality Undergraduate Programs: 2000–2001, Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 14:2, 4-8, DOI:10.1080/10963758.2002.10696728

Carlson, G. (2017). Be fierce: Stop harassment and take your power back. New York, NY: Center Street

Covert, B. (2014, Oct. 7). In The Restaurant Industry, ‘If You’re Not Being Harassed, Then You’re Not Doing The Right Thing’ Retrieved from https://thinkprogress.org/in-the-restaurant-industry-if-youre-not-being-harassed-then-you-re-not-doing-the-right-thing-9e8219a3318e/

Facts about sexual harassment. (n.d.). Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, retrieved from https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/publications/fs-sex.cfm

Fitzgerald, L. F., Drasgow, F., Hulin, C. L., Gelfand, M. J., & Magley, V. J. (1997). Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: a test of an integrated model. Journal of Applied psychology, 82(4), 578.

Fitzgerald, L. F., Magley, V. J., Drasgow, F., & Waldo, C. R. (1999). Measuring sexual harassment in the military: the sexual experiences questionnaire (SEQ—DoD). Military Psychology, 11(3), 243-263.

Giuffre, P. A., & Williams, C. L. (1994). Boundary lines: Labeling sexual harassment in restaurants. Gender & Society, 8(3), 378-401.

Holmes, R. (2001). Sexual harassment and the university. In Editor Francis, L. Sexual harassment as an ethical issue in academic life, pages 183-190. New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield

Industries at a glance: Leisure and hospitality, (n.d.). United States Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/iag/tgs/iag70.htm

Kensbock, S., Bailey, J., Jennings, G., & Patiar, A. (2015). Sexual harassment of women working as room attendants within 5-star hotels. Gender, Work & Organization, 22(1), 36–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12064

Kettl, P., Siberski, J., Hischmann, C. & Wood, B. (1993). Sexual harassment of health care students by patients. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services. 1993;31(7):11-13https://doi.org/10.3928/0279-3695-19930701-06

Koblin, J. (2016, July 12). Gretchen Carlson, former Fox anchor, speaks publicly about sexual harassment lawsuit. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/13/business/media/gretchen-carlson-fox-news-interview.html

Langelan, M. (1993). Back off!: How to confront and stop sexual harassment and harassers. New York, NY: Fireside

Madera, J.M., Guchait, P., & Dawson, M., (2018). Managers’ reactions to customer vs co-worker sexual harassment. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(2), 1211-1227. https://doi-org.ezproxy.mmu.ac.uk/10.1108/IJCHM-02-2017-0081

Matulewicz, K. (2015). Law and the construction of institutionalized sexual harassment in restaurants. Canadian Journal of Law & Society/La Revue Canadienne Droit et Société, 30(3), 401-419.

Matulewicz, K. (2016). Law’s Gendered Subtext: The Gender Order of Restaurant Work and Making Sexual Harassment Normal. Feminist Legal Studies, 24(2), 127-145.

Meyer, Z. (2017, December 18). 5 reasons why restaurants can be hotbeds of sexual harassment.

Retrieved from: https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2017/12/18/5-reasons-why-restaurants-can-hotbeds-sexual-harassment/950137001/

Morgan, N., & Pritchard, A. (2019). Gender Matters in Hospitality. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76 Part B, 38-44. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0278431918305061

Nelson, R. G., Rutherford, J. N., Hinde, K., & Clancy, K. B. (2017). Signaling Safety: Characterizing Fieldwork Experiences and Their Implications for Career Trajectories. American Anthropologist, 119(4), 710-722.

Nelson, R. (2018). Sexual Harassment in Nursing. AJN, American Journal of Nursing, 118(5), 19–20. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000532826.47647.42.

Poulston, J. (2008). Metamorphosis in hospitality: A tradition of sexual harassment. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27(2), 232-240.

Pryor, J. B., LaVite, C. M., & Stoller, L. M. (1993). A social psychological analysis of sexual harassment: The person/situation interaction. Journal of vocational behavior,42(1), 68-83.

Ram, Y. (2018). Hostility or hospitality? A review on violence, bullying and sexual harassment in the tourism and hospitality industry. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(7), 760-774. DOI: 10.1080/13683500.2015.1064364

Self, T. T., Adler, H., & Sydnor, S. (2016). An exploratory study of hospitality internships: Student perceptions of orientation and training and their plans to seek permanent employment with the company. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 15(4), 485-497.

The Glass Floor: Sexual Harassment in the Restaurant Industry (2014, Oct. 7) The Restaurant Opportunities Centers United Forward Together. Retrieved from http://rocunited.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/REPORT_The-Glass-Floor-Sexual-Harassment-in-the-Restaurant-Industry2.pdf

The 30 Best Hospitality Programs in the United States. (n.d.). The Best Schools retrieved from https://thebestschools.org/rankings/best-hospitality-degree-programs/

Zopiatis, A. & Constanti, P. (2012). Managing Hospitality Internship Practices: A Conceptual Framework. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 24:1, 44-51, DOI: 10.1080/10963758.2012.10696661