Connecting the Campus and the Community through Experiential Learning and Historic Innovation

Peggy Byers Fisher, PhD // Ball State University

Click Here to Download this Article

Abstract

Bringing a college or university campus, students, and local organizations together for a greater good has been happening for decades. This process involves much more than sending university students out to work or to volunteer with local organizations. The process includes placing students in for-profit and nonprofit organizations that have real needs and problems to solve. Helping students reflect upon their experience and learn from it is important to understand. This manuscript provides an innovative example of how one university is making history by connecting with the local school corporation and presenting a considerable number of opportunities for both students, faculty and staff to connect with and learn from. Additionally, it explains the difference between experiential learning and volunteering, examines the traditional models of experiential learning, and explores the benefits to the student, organization and campus.

In Stepping Forward as Stewards of Place: A Guide for Leading Public Engagement at State Colleges and Universities the American Association of State Colleges and Universities discusses what it means to be a steward of place (AASCU, 2002). The report discusses how linkages between institutions of higher education and communities can include outreach, applied research, technical assistance, policy analysis, learning programs, and service-learning, to mention a few. The important thing is that the “leaders translate the rhetoric of engagement into reality,” “how to walk the walk” and “talk the talk.” (AASCU, 2002). The report laments the lack of a clear definition of “public engagement” and offers the following: “The publicly engaged institution is fully committed to direct, two-way interaction with communities and other external constituencies through the development, exchange, and application of knowledge, information, and expertise for mutual benefit” (p. 9). Furthermore, it notes the importance of “getting all elements of the campus aligned and working together in support of public engagement efforts” (p.10).

INNOVATIVE PARTNERING

This mindset is clearly in motion at Ball State University (BSU) in Muncie, Indiana. BSU is engaged in an innovative, historic path as it connects on a deeper, more profound level with the Muncie community. In 2015, its commitment to the local community earned BSU the Community Engagement Classification from the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. This classification recognizes colleges and universities that demonstrate an institution-wide commitment to public service, civic involvement, and community partnerships (BSU, 2019).

Ball State President, Geoffrey S. Mearns, initiated his “Better Together” campaign in 2017 and “Spreading Our Wings” strategic planning process in 2018. Ball State has been engaging with the community for decades through internships, student teaching, educational initiatives, and service-learning opportunities. During the 2016-2017 school year over 3,000 students volunteered in over 130 community organizations, providing 57,762 hours of labor (Slabaugh, June 20, 2018). BSU’s most recent connections are through its Building Better Communities and Immersive Learning programs, and the new campaign, “Better Together.” To that end, the campaign started with three community forums: one on Neighborhoods and Education, a second on Arts and Culture, and a third on Economic Development in the fall of 2017 (BSU, 2018). The goal of these forums was to discover ways the campus and community could discuss struggles and opportunities to help each other and connect in more meaningful ways.

Campus and community groups are in the process of fleshing out new paths for collaboration based on these discussions. The first of these initiatives was a “Community Campus Experience” serving as a kickoff to BSU’s centennial anniversary celebration in June, 2018. Feedback from the forums suggests that community members are reluctant to come on campus because they don’t know where to park or where buildings are. For this event free parking was open across campus, there was food, games and entertainment, and visitors toured everything on campus from the auditoriums and planetarium, to the greenhouses, to the classrooms, and a host of other interesting locations. Its goal was to get community members familiar and comfortable with the campus and what we do.

Along with the initiatives mentioned above, BSU quietly, and to the surprise of many in the community and at the university, pursued legislative action that would give control of the local struggling Muncie Community School Corporation (MCS) that was under emergency management over to the university. In 1899, BSU was a “private teacher training school,” and in 1922 it became Ball Teachers College (BSU, 2019). It has a long history running elementary through high school initiatives, such as Burris Laboratory School and the Indiana Academy for Science, Mathematics, and Humanities. The university was ready and able to step in and help.

Taking over an entire distressed school corporation that was under emergency management had only been tried once before. Boston University ran Chelsea Public Schools for 20 years ending in 2008 (Seltzer, 2018). One main difference with the BSU collaboration is that MCS will remain financially independent from the university. On May 14, 2018 the Indiana General Assembly passed HB 1315—legislation that provided BSU with the “opportunity to appoint a new school board to manage the Muncie Community Schools” (G. S. Mearns, personal communication, May 14, 2018). On May 16th the BSU Board of Trustees passed a resolution accepting the responsibility to appoint a new school board to manage Muncie Community Schools. In effect, as of July 1st Ball State took over the local school corporation. Another “key difference” between the Boston University case and the BSU case is that the Chelsea School Committee “reserved power to override Boston University on policy matters affecting the whole district” (Seltzer, 2018). Mearns was quick to point out that this is a community partnership, not just a BSU initiative. He also discussed assembling a “large community engagement counsel” to help address ways BSU and the Muncie community can collaborate (Mearns, June 23, 2018).

“By marshalling BSU faculty, student and staff resources and mobilizing a coalition of external partners, the university ‘can change the trajectory’ of Muncie schools” (Slabaugh, May 14, 2018). To date, BSU has already generated more than $2.9 million in private support (G. S. Mearns, personal communication, May 16, 2018) for the school corporation. They have received a record 88 applications for seven positions on the new school board (Slabaugh, June 7, 2018) and interviewed 20 of those applicants (Slabaugh, June 11, 2018). The former school board will serve in an “advisory” capacity until its members’ terms expire (Slabaugh, June 13, 2018).

President Mearns is encouraging faculty to think of innovative and creative ways to actively participate in this endeavor while simultaneously attempting to garner student engagement. “The thinking is that this presents an opportunity to design some innovating programing in the district” (Seltzer, 2018). More specifically, this partnership is in the process of planning and implementing “audits of curriculum, instruction, and technology,” and “developing executive dashboards to monitor academic and financial indicators for the school system” (Slabaugh, February 19, 2019). President Mearns is clear that MCS teachers and staff are the “foundation of this partnership” (G. S. Mearns, personal communication, May 16, 2018) and that they are “valued” and “respected.” He promotes the true spirit of collaboration with the current school board members and families of MCS students as well. BSU is well aware that it needs to remain cognizant of the town-gown relationship. Mearns states “What we’re attempting to do is address a significant, profound challenge in Muncie and bring together the experience and expertise of our campus” (Seltzer, 2018). Ultimately, this partnership aims to be more than BSU fixing a problem, and then removing itself at some future date. BSU’s commitment, according to President Mearns, is long-term.

Exactly how this partnership will play out remains to be seen; details are emerging as new ground is being broken in the campus and community connection. Certainly, there will be bumps in the road and a steep learning curve. BSU’s initiatives through “Better Together” and the school corporation takeover, along with other community engagement programs, presents so many ways students and faculty can connect with the community through service-learning, internships, immersive learning, experiential learning, cooperative education and volunteering. For example, opportunities for engagement can come in the form of educational programs for teachers, resource development for the classroom, rebranding of the corporation, marketing, human resource development, policy revisions, early childhood development programs, long term planning, finance, training, fundraising, after school programs, sports management, promoting the arts, and politics.

DEFINING EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING

Programs whereby students are connecting with the community, such as those now underway at BSU, might be called different names and each has its own nuances, but the premise of learning-by-doing is the same for all. The 1993 National and Community Service Trust Act defined service-learning, in particular, as an educational experience that includes an organized service experience that meets actual community needs, is coordinated through a university or school, is integrated into students’ academic curriculum, makes continual links between the service experience and classroom content, provides structured opportunities for students to talk and/or write about the experience, and enhances what is taught in school (Schine, 1997). It is distinguished from basic volunteerism or community service because of its focus on integrating the service or work component with academic content and reflection. Jeffrey (2001) adds the importance of academic rigor, establishing learning objectives, and having “sound learning strategies” as part of these experiences. Similarly, internships and sometimes cooperative education are defined as a form of experiential learning that integrates knowledge and theory learned in the classroom, with practical application and development in a professional work environment (What is Cooperative Education, 2018, CEIA, 2015). Diambra, Cole-Zakrzewski and Booher (2004) highlight the importance of “adequate planning, structure, supervision, monitoring and opportunities for ongoing reflection” as part of a successful internship experience (p. 211).

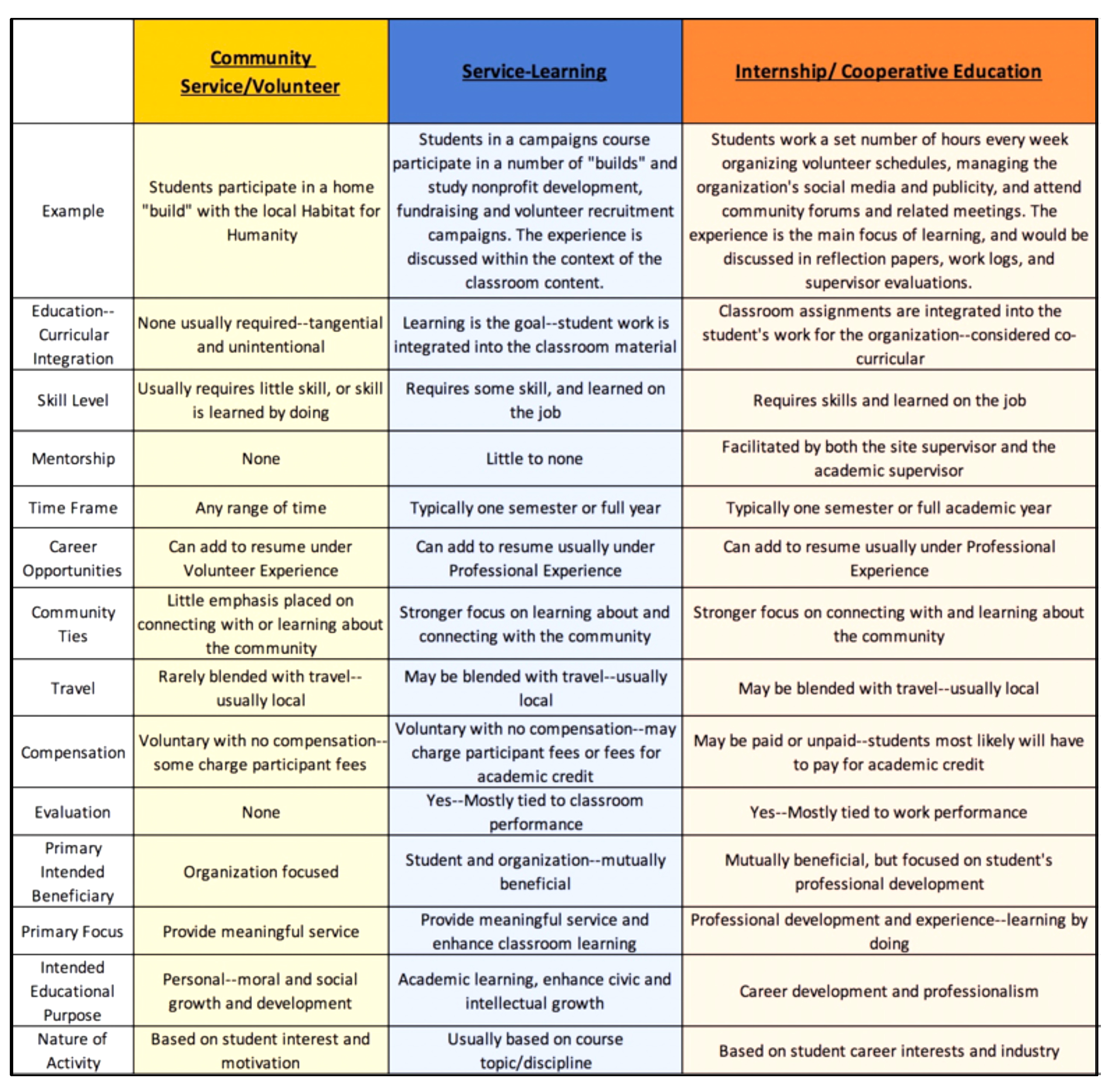

Table 1 illustrates some of the differences between volunteering, service-learning and internships (Fisher, 2018).

DEVELOPMENT OF EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING

According to Sweitzer and King (1999), experiential learning has its roots in the apprenticeship system of the medieval times. Professional schools and training programs required “practical experiences as integral components” of these programs (p. 11). This experience sets the stage for what we now refer to as “internships.” The call for “public engagement” is almost a return to our “roots and a reengagement of the core purpose of higher education” (Hoffman, 2016). In more recent times, according to the Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (CAS), the partnership between community and campus became more prominent during the Civil Rights Movement and the social activism of the 60s and 70s. There was intentional engagement regarding the social, political, and economic strife of the community and institutions of higher education. University organizations began to focus on neighborhood development and outreach programs.

The 80s witnessed student activism with the birth of COOL—The Campus Outreach and Opportunities League—to promote community involvement with students. In 1985 Campus Compact created a coalition of university and college presidents committed to enhancing the public purpose of higher education. Gorgal (2012) discusses the growth of service-learning and civic engagement efforts during the 1990s noting that higher education had renewed its commitment to community and democracy.

During the 2000s the scope of experiential learning widened to include more service-learning courses and added an array of “course-based strategies” and “high-impact pedagogies” geared towards improving citizenship (CAS). These include opportunities such as alternative spring breaks, community-based research, campus service days, internships, political engagement, experiential education, immersive learning, and service learning. Campuses also began to “document” the accomplishments of these programs which lead to the development of more formal academic programs and structures to support faculty and students. Often these offices can be found under departmental internships, academic affairs or student affairs (Sponsler & Hartly, 2013).

Not all experiences out of the classroom are educative, however. Kolb (1984) emphasized that these experiences still need to be organized and geared toward learning. The learning context must engage students’ development through real-world problems and conflicts that the students must solve. “For real learning to happen, students need to be active participants in the learning process rather than passive recipients of information given by a teacher (Sweitzer & King, 1998, p. 11). The teacher’s role is to guide and facilitate the learning and coach students through the experience (Garvin, 1991).

MODELS OF EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING

Traditionally, three models have guided experiential learning: group process, simulation-games and field experience (Wagner, 1992). The group process model builds upon interactions among the group members, the group “process” itself. Sensitivity training workshops were a popular form of this in the 70s. Individuals learn by analyzing the interaction process within the setting itself. The simulation-games approach relies on “gaming” activities to engage students in specific patterns of interaction. The games are structured in a way that encourages these patterns. For example, students might play the game Scrabble in competition against each other, then in cooperation with each other as they share their letters. Students learn by making connections between the gaming situation and real-world problems. The field experience model emphasizes integrating academic content with off-campus student experiences, much like a course on persuasion that assists with a political campaign. Learning comes through the value of participating in non-academic settings (Wagner, 1992).

Kolb’s Experiential Learning Model (1984) is a commonly used framework for developing and implementing service-learning curricula and is based on widely accepted learning theories (Pritchard & Whitehead, 2004). In sum, Kolb’s cycle recognized that reflection transforms the service into new and applicable understanding. Service is the experience, and the reflection impacts the students’ education, along with skills and values. More contemporary frameworks address collaborative and social processes important in the learning experience. For example, The Collaborative Service-Learning Model (Pritchard & Whitehead, 2004) builds upon Kolb’s (1984) work and integrates the elements of “involvement, commitment to shared purposes, planning, teamwork, team consultation, reflexive dialogue and consummatory activity” (p. 12). Fiore, Metcalf and McDaniel (2007) suggest the Transfer Appropriate Process Theory (TAP) can be used to “support an understanding of experiential learning within a variety of different domains” (p. 37). They suggest that in the context of experiential learning, TAP theory addresses the synchronization between the thought processes engaged during learning and the eventual use of that learning.

While internships can be done at nonprofit or for-profit organizations, at BSU most often service-learning is done with nonprofit entities. “Service is fundamental to our own United States culture” (Pritchard & Whitehead, 2004, p. 1). “Civic Participation” and “social problem-solving” are embedded in our social fabric (p. 1).

BENEFITS FOR CAMPUS, STUDENTS AND COMMUNITY

Campus and Faculty

In the report, “The Future of Learning: How Colleges Can Transform the Educational Experience,” the Chronicle of Higher Education (2018) discusses how to “remove barriers, experiment, and innovate to prepare for the future of learning.” Immersive learning and active learning are presented as important ways to improve education. Experiential learning programs, including internships and service-learning, are considered controversial at some institutions (Sweitzer & King, 1998). They can be expensive to administer, a “management nightmare” for some universities (p. 12), and their scholarship is often met with skepticism. However, this approach to learning has evolved into a disciplined and goal-focused form of education. It continues to thrive because of its potential.

Institutions have recognized that their regional and local communities offer great opportunities, serving as “learning laboratories” that enhance classroom instruction, research, and creative endeavors (AASCU, 2002, p. 11). These connections are “powerful vehicles to affirm institutional mission; to connect teaching, research, and outreach with the ‘real world’ for faculty and students; to bring knowledge in service to society; and to provide accountability for public funds while extending public dollars and leveraging extramural funds” (p. 11).

While institutions of higher education are not “corporations” per se, they can still posture themselves as supporters of corporate social responsibility. Our “consumers” include current and future students, parents, donors, alumni, employers and community members looking for more than just a piece of paper documenting students have passed their coursework. These “consumers” want to see the tangible evidence of student achievement in the community. Furthermore, they want to understand and be involved in the options for students to engage outside the classroom and make those important community contributions. Fallon (2017) suggests that “undertaking socially responsible initiatives is truly a win-win situation. Not only will your company (university) appeal to socially conscious consumers and employees, but you’ll also make a real difference in the world.”

Along with the campus, individual faculty benefit as well. For example, managing internships for 30 years as both a faculty supervisor and a site supervisor, and facilitating immersive learning projects for 10 years has personally changed the way I teach. I love bringing situations from those experiences into the classroom and offering them up for analysis and discussion. Most often those discussions are framed as “This is what happened. What could we have done differently?” Students appreciate hearing about real-life situations, especially when the teacher and their counterparts are directly involved.

Student

Melchior and Bailis (2002) discuss how experiential learning can have a positive impact on students’ “civic, academic, social and career development” (p. 202). They further advocate that the impact on students is directly tied to the quality of these programs. These authors present evidence from three major national service-learning initiatives: Serve-America, Active Citizenship Today, and Learn and Serve. While their focus is on middle and high school students, it is also relevant to college-age students.

We can look at four specific benefits of experiential learning for the student. First, Pritchard and Whitehead (2004) discuss how the process can enhance students’ cognitive and intellectual development. Experience-based activities can stimulate their “intellectual capacities” (p. 4). A second benefit is the potential to improve students’ academic achievement. Pritchard and Whitehead (2004) note how students who engage in these experiences may be more motivated to learn, and therefore perform better in their academic subjects. A third benefit is the “potential for strengthening students’ citizenship education, their sense of community responsibility” (p. 4). The fourth benefit is the potential for developing more active problem-solving skills in students, rather than focusing on information consumption and “imitative learning” (p. 5). This could lead to re-thinking the educational process across college campuses. Additionally, The Center for Community-Engaged Learning (2018) at the University of Minnesota suggests students can benefit academically, personally and professionally through increased understanding of course content, examining values and beliefs, developing critical thinking and problem-solving skills, connecting with professionals and community members, and learning more about social issues. Weintraub (2018) notes that “students are no longer simply receivers of knowledge but active learners who engage with the material and link their experiences with the course content.” They learn that they can be “agents of change” and “identify the interconnectedness of their lives with the lives of others” (p.25). Connecting with the community outside the walls of a traditional classroom can encourage interactive learning strategies, give new dimensions to classroom discussion, engage students, provide networking opportunities, give insight into community issues, and develop civic and leadership skills (Center for Community-Engaged Learning, 2018).

Finally, and probably the most important from the students’ perspectives, is that the experiences give them practical experience to put on their resumes. They are able to talk about what they did and what they learned in job interviews and on cover letters. Many job descriptions list “experience” as a preferred, if not mandatory, requirement. The National Association of Colleges and Employers reports that “Nearly 91 percent of employers in the Job Outlooks 2017 survey prefer that their candidates have work experience” (NACE, 2017). These experiences are key for students entering the job market. Experiential learning programs give students the opportunity to attain that experience in a learning context.

Organization/Community Partner

Community partners receive valuable service and support (Why Use Service Learning?, 2018), and the opportunity to address specific needs. They also receive additional resources to achieve organizational safety and human resource goals, new energy, perspectives and enthusiasm, help in preparing future leaders, access to university resources, and increased awareness of important organizational issues. It also helps create the potential for additional partnerships and collaborative efforts between the organization and the campus (Benefits of Service-Learning, 2018, Center for Community-Engaged Learning, 2018). McCarrier (1992) discusses how students’ enthusiasm brings a “freshness” to the job that more than makes up for their initial inexperience.

Bandy (2018) suggests that community partners receive “satisfaction with student participation, valuable human resources needed to achieve community goals, new energy, enthusiasm and perspectives applied to community work, and enhanced community-university relations.”

SUMMARY

Connecting the campus with community is not a new concept. Public institutions of higher education have considered it part of their purpose and mission for centuries. Since medieval times students have been expected, and even required to go into their communities and learn by practicing their trades. This manuscript looked at how one university is making history by connecting with the local school corporation. It discusses the difference between experiential learning and volunteering, the traditional models of experiential learning, and the benefits to the student, organization and campus.

Ball State University is currently positioning itself to have a significant impact on the local school corporation that will involve connecting students and faculty with struggling schools. This endeavor will provide a plethora of experiential learning opportunities including service-learning, internships, immersive learning, and volunteering that students, faculty, staff and the community can benefit from.

REFERENCES

AASCU (2002). Stepping Forward as stewards of place: A guide for leading public engagement at state colleges and universities. Retrieved from http://www.aascu.org/publications/stewardsofplace/.

Bandy, J. (2018). What is service-learning or community engagement. Retrieved from //cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/teaching-through-community-engagement/.

Benefits of Service-Learning (2018). Service-Learning Leeward Community College. Retrieved from www2.leeward.hawaii.edu/servicelearning/benefits.htm.

BSU (2018). Retrieved from cms.bsu.edu/about/administrativeoffices/president/better-together.

BSU (2019). Retrieved from www.bsu.edu/about/rankings.

BSU (2019). Retrieved from https://www.bsu.edu/about/history.

CAS (2018). Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education www.cas.edu.

CEIA (2015). Cooperative Education and Internship Association. http://www.ceiainc.org/knowledge-zone/experience-magazine/ [pdf]. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

Center for Community-Engaged Learning (2018). Benefits of service-learning. University of Minnesota. Retrieved from www.servicelearning.umn.edu/info/benefits.html.

Chronicle of Higher Education (2018). The future of learning: How colleges can transform the educational experience. Retrieved from https://store.chronicle.com/products/the-future-of-learning-how-colleges-can-transform-the-educational-experience.

Diambra, J. F., Cole-Zakrzewshki, K. G., & Booher, J. (2004). A comparison of internship stage models: Evidence from intern experiences. Journal of Experiential Education, 15(1), 191-212.

Fallon, N. (2017, December 29). What is corporate social responsibility? Business News Daily. Retrieved from www.businessnewsdaily.com/4679-corporate-social-responsibility.html.

Fiore, S., Metcalf, D., & McDaniel, R. (2007). Theoretical foundations of experiential learning. In M. Silberman (Ed.), The handbook of experiential education (pp. 33-58). NY: Wiley.

Fisher, P. B. (April, 2018). Connecting Students with Nonprofit Opportunities: Looking at Community Service, Service Learning and Internship. Presented at the Central States Communication Association, Milwaukee, WI.

Garvin, D. A. (1991). Barriers and gateways to learning. In C. R. Christensen, D. A. Garvin, & A. Sweet (Eds.), Education for judgement (pp. 3-13). Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Georgia Tech Center for Career Discovery and Development (2018). What is cooperative education? Retrieved from https://career.gatech.edu/what-cooperative-education.

Gorgal (Sponsler), L.E. (2012). Understanding the influence of the college experience on students’ civic development. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Pennsylvania.

Hoffman, A. J. (2016, September 5). Why academics are losing relevance in society-and how to stop it. The Conversation. Retrieved from www. theconversation.com/why-academics-are-losing-relevance-in-society-and-how-to-stop-it-64579.

Jeffrey, H. (2001). (Ed.), Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning: Service-Learning Course Design Workbook. University of Michigan: OCSL Press, pp. 16-19.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

McCarrier, J. T. (1992). Intern program yields dividends to students, firm. In A. Ciofalo (Ed.), Internships: Perspectives on experiential learning (pp. 259-263). FL: Kreiger Publishing Company.

Mearns, G. (June 23, 2018). Retrieved from https://www.thestarpress.com/videos/news/local/2018/06/13/mearns-gives-his-thoughts-muncie-community-schools-public-forum/36000355/.

Melchior, A. & Bailis, L. N. (2002). Impact of service-learning on civic attitudes and behaviors of middle and high school youth. In A. Furco & S. H. Billig (Eds.), Service-learning: The essence of the pedagogy (pp 201-222). CT: Information Age Publishing.

NACE (2017). Employers prefer candidates with work experience. Retrieved from https://www.naceweb.org/talent-acquisition/candidate-selection/employers-prefer-candidates-with-work-experience/.

Pritchard, F. F., & Whitehead, III, G. I., (2004). Serve and learn: Implementing and evaluating service-learning in middle and high schools. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Schine, J. (1997). Looking ahead: Issues and challenges. In K. J. Rehage (Series Ed.) and J. Schine (Vol. Ed.), Ninety-sixth yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, Part 1. Service-learning (pp. 186-199). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Seltzer, R. (March 8, 2018). A university-run school district? Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/03/08/ball-state-university-poised-historic-takeover-school-district-muncie-ind.

Slabaugh, S. (May 14, 2018). House, Senate OK Ball State takeover of Muncie school. The Star Press. Retrieved from www.thestarpress.com/story/news/local/2018/05/14/house-oks-ball-state-takeover-muncie-schools/606744002/.

Slabaugh, S. (June 7, 2018). Ball State provides the names of 88 Muncie School Board candidates. The Star Press. Retrieved from www.thestarpress.com/story/news/local/2018/06/06/ball-state-provides-names-88-muncie-school-board-candidates/673674002/.

Slabaugh, S. (June 11, 2018). Ball State picks 16 finalists for Muncie schoolboard. The Star Press. Retrieved from www.thestarpress.com/story/news/local/2018/06/11/ball-state-university-picks-16-finalists-muncie-school-board/689901002/

Slabaugh, S. (June 13, 2018). Warner leaves school board. The Star Press. Retrieved from http://munciestarpress.in.newsmemory.com/?token=ae3643501289bb0db9ec7a07f29d2e6a&cnum=3178524&fod=1111111STD&selDate=20180613&licenseType=paid_subscriber&.

Slabaugh, S. (June 20, 2018). Ball State provided with ‘big, bold’ ideas. The Star Press. Retrieved from http://munciestarpress.in.newsmemory.com/?token=d397279ba1167de9727349343d69b5a3&cnum=3178524&fod=1111111STD&selDate=20180620&licenseType=paid_subscriber&.

Slabaugh, S. (February 19, 2019). BSU’s liaison to MCS retires, new council to assume duties. Retrieved from https://www.thestarpress.com/story/news/education/2019/02/19/bsus-liaison-mcs-retires-new-council-assume-duties/2913561002/#.

Sweitzer, H. F., & King, M. A. (1999). The successful internship: Transformation & empowerment. NY: Brooks/Cole Publishing.

Wagner, J., (1992). Integrating the traditions of experiential learning in internship education. In A. Ciofalo (Ed.), Internships: Perspectives on experiential learning (pp. 21-35). FL: Kreiger Publishing Company.

Weintraub, S. C. (2018). Service-learning as an effective pedagogical approach for communication educators. Journal of Communication Pedagogy, 1(1), 24-26. DOI: 10.31446/JCP.2018.07

Why Use Service Learning (2018). Retrieved from https://serc.carleton.edu/introgeo/service/why.html